Bring It On & The Racial Politics of a Bygone Era

Yassine reviews a cheerleading movie

Bring It On (2000) is a good movie. I had no idea this was true! I’m not going to film school nerd about this except to cite this amazing series of match cuts. Rather, I want to talk about its racial politics, and the many ways this movie couldn’t have been made today (and not just because of the casual fag! insults).

The central conflict is between two cheerleading teams: the San Diego Rancho Carne High (RCH), whose students are unimaginably rich and whose cheerleading team is almost entirely white save for the one Token Asian, and the East Compton Clovers, who are poor financially but rich in melanin.

RCH has been on a remarkable winning streak, pursuing their sixth consecutive national title. Through a series of events, the team finds out their previous captain had been stealing their award-winning cheerleading routines — from the Clovers! The Clovers always knew about the choreography heist but lacked the resources to compete nationally. So they spectated their own routines from the bleachers as RCH won year after year.

The film is not subtle about its agenda, but it’s worth ruminating on the specific ways it depicts racial tension. The Clovers are the underdogs, but the movie makes it clear they are tremendously talented — there is no doubt about their creative and physical prowess in cheerleading. Their exclusion from the national competition isn’t due to overt melanin aversion. There’s no sneering judge dismissing their style as ‘ghetto’ or ‘inappropriate’ for the competition, no concerned administrator wondering aloud about their academic eligibility, no security guard hassling them at competitions.

Instead, their only barrier is economic: they can’t afford the entry fee. The movie trusts audiences to recognize that an unlevel playing field is injustice enough.

The Clovers are proud, resourceful, fully cognizant of the challenges they face, and at peace with having to work twice as hard for half the recognition. There’s a quiet dignity in how they’ve channeled their frustration into excellence, refusing to let systemic barriers diminish them.

There’s an interesting contrast in how the Clovers accept help. When the new RCH captain (Kirsten Dunst), offers to pay their entry fee, the Clovers reject it. Accepting help from her would have implied that RCH’s theft was forgiven, and could have cemented a racially subservient relationship.

In contrast, they do accept a black talk show host’s offer to pay their entry fee. This echoes an increasingly antiquated ethos of an independent black resilience (most prominently aligned with Malcolm X) that is not dependent on fickle white generosity. The Clovers are willing to accept outside help after all, but only if — from their perspective — it is sufficiently sanitized of racial baggage. Their selectiveness is undeniably a setback, materially speaking, but at least it’s rooted in dignity and self-determination. Perhaps it’s a worthwhile trade-off.

Few terms are as mis/over-used as ‘institutional racism’ and I don’t intend to resurrect it. It does try to grasp at something very real: many institutional barriers get in the way of individual flourishing, and these barriers can correlate with race, even in the absence of a direct causal nexus. The Clovers, for many reasons related to their race, were held back by lack of capital, but all they asked for was for a chance to be judged on their merits.

The restrained messaging of this morality tale is in sharp contrast to much more recent oeuvres. These works, inspired by real histories of exclusion and violence, choose to depict racial oppression by dialing up the absurdity and exaggeration. The TV show Lovecraft Country (2020) is set in the era where race-based discrimination was legal, and black motorists relied on specialized guides such as The Negro Motorist Green Book (briefly depicted in the show) to know which areas would refuse them food and lodging or subject them to arbitrary arrests.

In the first episode, a black family stops at a diner in 1950s Massachusetts (Massachusetts!), where they’re met with leery and suspicious looks from the all-white residents. The subtle tension quickly ramps up into a cartoonish chase sequence as shotgun-toting locals pile into a pickup truck, careening through traffic in a frenzied and ultimately self-destructive pursuit.

The show took a genuine historical fear and turned it into a Tom & Jerry chase scene, the one where he monomaniacally crashes into a wall and everyone laughs. Lovecraft Country drew obvious inspiration from Get Out (2017), where racism was literalized as body-snatching. The Guardian’s (presumably unironic) review noted:

The villains here aren’t southern rednecks or neo-Nazi skinheads, or the so-called “alt-right”. They’re middle-class white liberals. The kind of people who read this website. The kind of people who shop at Trader Joe’s, donate to the ACLU and would have voted for Obama a third time if they could. Good people. Nice people. Your parents, probably. The thing Get Out does so well – and the thing that will rankle with some viewers – is to show how, however unintentionally, these same people can make life so hard and uncomfortable for black people. It exposes a liberal ignorance and hubris that has been allowed to fester. It’s an attitude, an arrogance which in the film leads to a horrific final solution, but in reality leads to a complacency that is just as dangerous.

This was a movie where a cadre of white liberal suburbanites are achieving immortality through surgical brain transplants conducted on randomly kidnapped black men! What exactly is the intended message here? That black people should stay away from Trader Joe’s locations lest they get unwittingly transformed into mindless thralls by white Obama voters?

The absurdity behind the film’s central metaphor presupposes that white people are so blinded by their privileged perspective that they’re constitutionally incapable of understanding how insidious racism really is. But instead of raising the salience of the message, it undermines it by relegating racial oppression to the realm of body-snatching horror fiction rather than grounded social commentary.

Artistic hyperbole is undermining even when deployed in the opposite direction. BlacKkKlansman (2018) is a critically acclaimed movie that I couldn’t get through. Though based on a true story, Spike Lee couldn’t help but depict the KKK as a bunch of incompetent, idiotic, goofball rednecks. If they’re such a laughingstock, such a clown car of an outfit, why would law enforcement ever care to infiltrate them?

You’ll notice the examples I listed all came out during the height of Wokism, and their messaging is a reflection of the times, just as Bring It On is a reflection of its time.

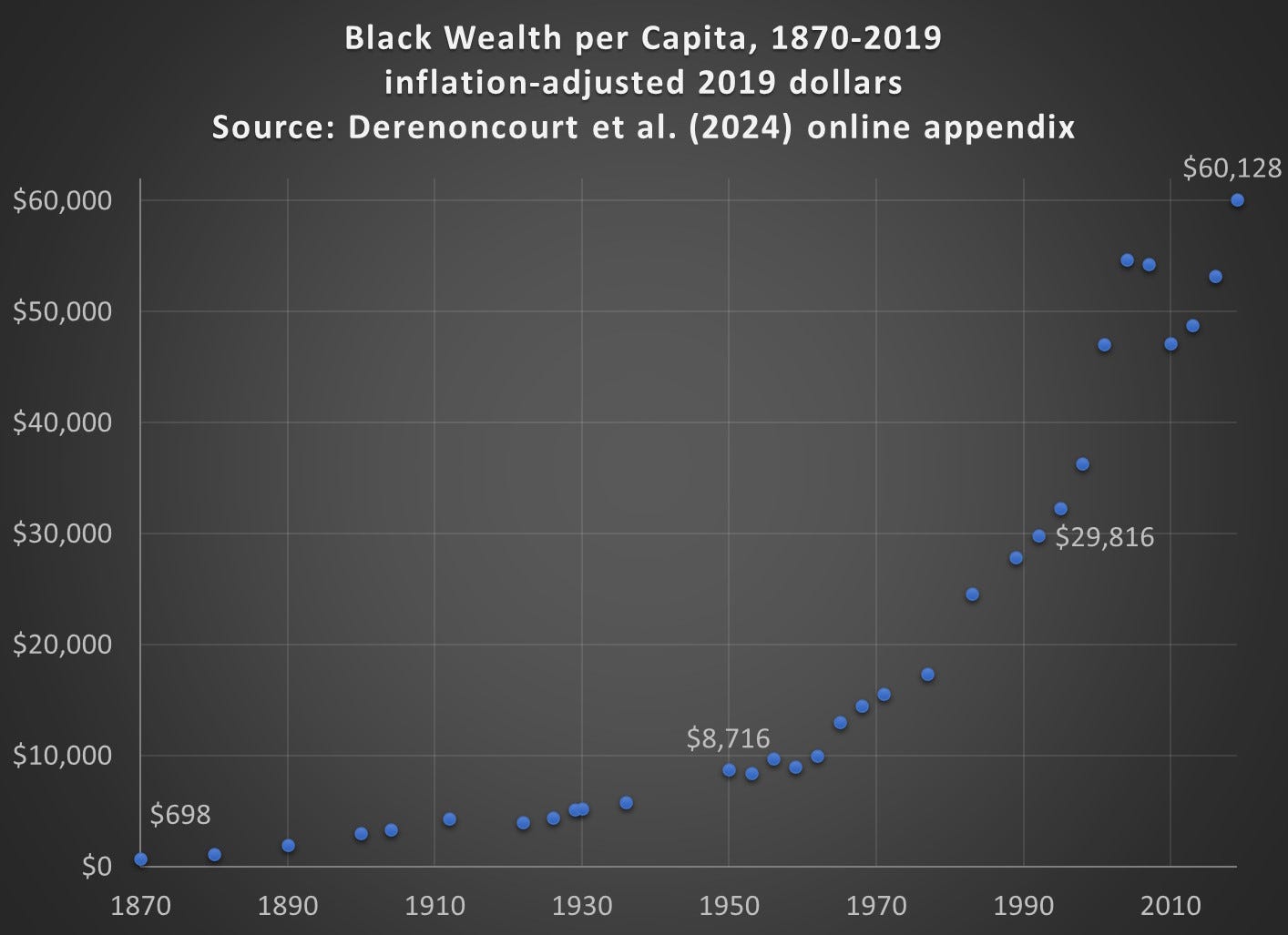

One of the core aspects of Wokism is a refusal to accept that racial oppression could ever get better, even though it unquestionably did. Pick whatever metric you want to define oppression by, but inflation-adjusted per capita black wealth continues to skyrocket for example:

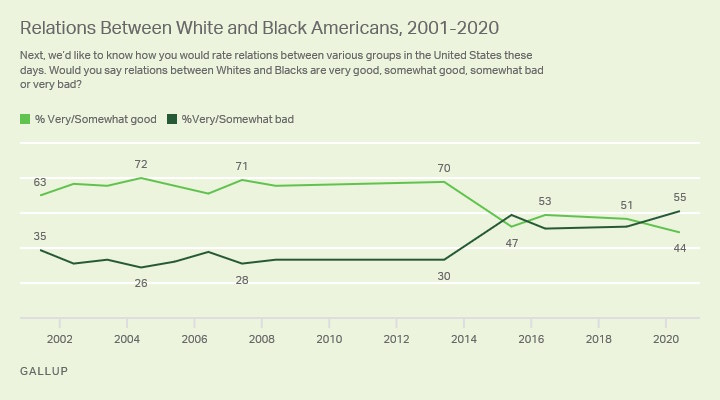

And yet, an unprecedented pessimism has taken hold starting around 2015. In 2020, the portions of Americans who said that race relations were bad nearly doubled to 55%, compared to 26%-30% in previous years:

In the absence of gross violations to point to, Wokism resorted to microscopic diagnostic tools, unearthing microaggressions that were previously invisible to the naked eye. Yet, paradoxically, dramatic depictions compensated in the other direction: simultaneously dressing down the KKK as inept idiots, while also presenting American racism as a cult of suburban body snatchers.

What I appreciate about Bring It On is that the central racial tension is subtle but grounded in reality. It illustrates that injustices don’t always have obvious answers or villains. It also shows that even supposed victims of institutional challenges can set themselves back, such as when they pursue pride at their own expense.

It’s remarkable that a silly, self-aware teen comedy about cheerleading can have something to say about race that is more nuanced, thoughtful, and meaningful than many recent critically acclaimed films. This was not due to an unprecedented burst of filmmaking genius, but unfortunately the result of the racial discourse suffering a regressive setback.

Also, I’m not saying this only because I married a former cheerleader, but the sport is severely underappreciated as an athletic feat. The double-triple jumps and pirouettes in this compilation video are formidable achievements. They represent countless hours, pain, and perhaps a statistical paralysis.

I don't have the data to back it up (aka, feel free to ignore this comment), but I'm suspicious that there might be a more general trend here.

For a large class of societal problems, the general approach has been funnel energy into building awareness, channeling that awareness into action, and using that action to build yet more awareness.

It seems plausible to me, that an unintended side effect of this activism funnel could be that awareness of an issue is inversely proportional to how bad the issue remains.

As a trans person in a non-american country, where HRT is easy to access and societal stigma is low, I've found it notable how trans activism seems to be at it's peak now. Just when it's least needed.

I suspect that might be the case with lots of movements.

“U, G, L, Y, you ain't got no alibi,” regularly breaks out in my head unprompted because of that film.