In This House, We Believe in Gender Stereotypes

Strap on, this is going to be a long one.

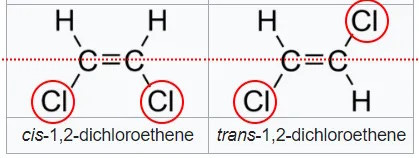

If you’ve ever been curious about the etymology of cis and trans as prefixes, just know they’re Latin for “the same side of” and “the other side of”, respectively. These prefixes are widely used in organic chemistry to distinguish between molecules that have the exact same atoms with a different spatial arrangement. Notice, for example, how in the cis isomer below on the left, chlorine atoms are oriented toward the “same side” as each other, but on the “other side” of each other in the trans isomer:

The dashed line is just me simplifying the geometric comparison plane (the E-Z convention is much more precise in this respect), but regardless, this is meant only to illustrate how talk of cis or trans is necessarily one of relative positioning. A single solitary point floating in space cannot be described as the same or other “side” of anything when there is nothing else to contrast it against.

Now this is just organic chemistry, not real life, but the cis/trans convention is applied consistently elsewhere. In the context relevant to this post, “sex” and “gender” are the two anchor points — the two chlorine atoms in the dichloroethene molecule of life — and their relative resonance/dissonance relative to each other is the very definition of cis/trans gender identity. To avoid any ambiguity, I use sex to refer to one’s biological role in reproduction (strictly binary), while gender is the fuzzy spectrum of sex-based societal expectations about how one is supposed to act. If your sex and gender identity “align”, then you are considered cis; if they don’t, then you are trans. Same side versus other side.

But what does it mean for sex and gender identity to “align”? There is an obvious answer to this question, but it is peculiarly difficult to encounter it transparently out in the wild. For reasons outlined below, I will argue that the elusiveness is completely intentional.

More than two years ago I wrote a post that got me put on a watch list, called Do Trans People Exist?. The question mark was barely a hedge and the theory I outlined remains straightforward:

I’m starting to think that trans people do not exist. What I mean by this is that I’m finding myself drawn towards an alternative theory that when someone identifies as trans, they’ve fallen prey to a gender conformity system that is too rigid.

Two years on and I maintain my assertion remains trivially true. One change I would make is avoiding the “fallen prey” language because I have no idea whether the rigidity is nascent to and incubated by the trans community (for whatever reasons), or if it’s just an enduring consequence of society’s extant gender conformity system (no matter how much liberal society tells itself otherwise). If you disagree with my assertion, it’s actually super-duper easy to refute it; all anyone needs to do is offer up a coherent description of either cis or trans gender identity void of any reference to gender stereotypes. But I’d be asking for the impossible here, because the essence of these concepts is to describe the resonance or dissonance that exists between one’s biological reality (sex) and the accordant societal expectations imposed (gender). Unless you internalize or assimilate society’s gender expectations, unless you accede to them and capitulate that they’re worth respecting and paying attention to as a guiding lodestar, concepts like “gender dysphoria” are fundamentally moot. A single point cannot resonate or clash with itself, as these dynamics necessitate interaction between distinct elements.

The position I’m arguing is nothing new. The philosopher Rebecca Reilly-Cooper (at Warwick then, previously at Oxford) had already established the incoherencies inherent within this framework conclusively and with impeccable clarity in this lecture she gave way back in 2016 (website form). It’s wild how her arguments remain perfectly relevant today, and if anyone has attempted a refutation I have not encountered it. And yet this remains a controversial position to stake, but not because it’s wrong. Rather, I believe, it’s because of how insulting it is to be accused of reifying any system of stereotypes nowadays.

In case it needs to be said, stereotypes can occasionally offer useful shortcuts, but their inherent overgeneralization risks flattening reality into inaccuracy. The major risk relevant to this discussion is when stereotypes crystallize into concrete expectations, suffocating individual expression with either forced conformity due to perceived group membership, or feelings of alienation due to perceived incongruence. The indignation to my position is also understandable given how the foundational ethos of the queer liberation movement was a rejection of gender normativity’s constraints.

You’re not obligated to take my word for this, but I do tend to feel an immense discomfort whenever I hold a position that is purportedly controversial, and yet I’m unable to steelman any plausible refutations — a sense of “I must be missing something, it can’t be this obvious” type deal. I did try to bridge the chasm of inscrutability when I wrote What Boston Can Teach Us About What a Woman Is. My plea to everyone was to jettison the ambiguous semantic topography within this topic and replace it with concrete specifics:

To the extent that woman is a cluster of traits, I struggle to contemplate a scenario where communicating the cluster is a more efficient or more thoughtful method of communication than just communicating the specific pertinent trait. Just tell me what you want me to know directly. Use other words if need be.

Because right now it’s a complete fucking riddle to me if someone discloses that they “identify as a woman” or whatever. What, exactly, am I supposed to do with this new information? Suggesting that stereotypes are the referent is met with umbrage and steadfast denials, but if not that, then what? Over the years I’ve tried earnestly to learn by asking questions and seeking out resources, and what I’ve repeatedly experienced is a marked reluctance to offer up anything more than the vaguest of details.

The ambiguity I’m referring to isn’t absolute, however, and there are two notable exceptions worth briefly addressing: body modifications and preferred pronouns.

Sex does not only determine whether an individual produces large or small gametes — an entire armory of secondary characteristics comes along for the ride, whether you like it or not. If a female happens to be distressed by their breasts and wants them removed, you could describe this scenario in two very different ways. One is that this person “identifies as a man” and their (very obviously female) breasts serve as a distressing monument that something is “off”. The other way is that this person is simply distressed by their breasts, full stop, without any of the gender-related accoutrements. [These two options are not necessarily exhaustive, and I’m open to other potential interpretations.]

Is there any difference between these two approaches? The first framework adds a multitude of vexing, unanswerable questions (Does comfort with one’s secondary sex characteristics require some sort of “affirmation gene” that trans people unfortunately lack? Is the problem some sort of mind/body misalignment? If so, why address one side of that equation only? Etc.) within an already overcomplicated framework. The other concern here is if the gender identity becomes prescriptive, where an individual pursues a body modification not for whatever inherent qualities it may have, but rather because of some felt obligation to “complete the set” for what their particular identity is supposed to look like.

The second framework (the one eschewing the gender identity component) would not dismiss the individual’s concerns and would be part of a panoply of well-established phenomena of individuals inconsolably distressed with their body, such as body integrity dysphoria (BID), anorexia, or muscle dysphoria. The general remedies here tend to be a combination of counseling and medication to deal with the distress directly, and only in rare circumstances is permanent alteration even considered. I imagine there is some consternation that I’ve compared gender dysphoria with BID, but I see no reason to believe they are qualitatively different and welcome anyone to demonstrate otherwise. Regardless, I subscribe to maximum individual autonomy on these matters, and so it’s not any of my business what people choose to do with their bodies. The point here is that preferences about one’s body (either aesthetic or functional) exist without a reliance on paradigm shifts of one’s “internal sense of self”. If someone wants to, for example, bulk up and build muscle, they can just do it; it’s nonsensical to say they first need to “identify” as their chosen aspiration before any changes can occur.

The other exception to the ambiguity around what gender identity means is pronoun preference. Chalk it up to [whatever]-privilege, but I concede I do not understand the fixation on pronouns. The closest parallel I can think of are nickname preferences, but unlike nicknames, pronouns almost never come up in two-party conversations, so it’s difficult to see why they would be any more consequential. I personally accommodate pronoun preferences out of politeness (and I suspect almost everyone else does as well), the exact same way I would accommodate nicknames out of politeness. If I happen to refer to my friend using frog/frogs pronouns, it’s not because I believe they’re actually a frog; I’m just trying to be nice and avoid getting yelled at. Regardless of the intent behind them, pronoun preferences are a facile and woefully incomplete account for what we’re warned are suicidal levels of distress around one’s incongruent gender identity, so this can’t be the whole story.

So on one extreme you have potentially invasive body modifications that are at least commensurate with the seriousness of the distress expressed, and on the other side you have the equivalent of a nickname preference that is relatively facile to accommodate. In between these two pillars, however, is a conspicuous vacuum of silence. My conclusion is that this missing middle is really just gendered stereotypes, but nobody wants to admit something so laughably antiquated out loud.

Well, almost nobody.

I’ve had this post sitting in my drafts for months largely because of an ever-present concern that I was unfairly shining a spotlight on the craziest examples from the trans-affirming community. My perennial goal with any subject is to avoid weakmanning, but with this issue I have no idea how to draw the contours and discern what arguments are representative and thus fair game to critique.

The lack of contours means I can’t prove this next part conclusively, but I noticed a shift over time regarding which talking points were most common. The perennial challenge for this camp remains the logical impossibility of harmonizing the twin snakes of “trans people don’t owe you passing” and “trans people will literally kill themselves if they don’t pass”. At least as late as 2018, there was more of an apparent comfort with leaning more toward openly reifying gendered roles and expectations. For example, in this Aeon magazine dialogue between trans philosopher Sophie Grace Chappell and gender-critical feminist Holly Lawford-Smith, Chappell uses the word script in her responses a whopping forty-one times.

But by far the most jaw-dropping example of this comfort comes from a lecture by Dr. Diane Ehrensaft, currently the head psychologist for the UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospitals’ gender clinic. When a parent asked how to know if a baby is trans, Dr. Ehrensaft literally said that a baby throwing out a barrette is a “gender signal” the baby might not really be a girl, the same way another baby opening their onesie is a signal they might be a girl. Seriously, watch this shit:

This is such a blatantly asinine thing to say that it depresses me to no end that the auditorium didn’t erupt in raucous laughter at her answer. I don’t even know how to respond to it. Maybe it bears repeating that babies are dumb. At any given moment, the entirety of a baby’s cognitive load is already stressed over having to decide between shitting and vomiting. Dr. Ehrensaft conjures up this tale about how dumb babies are able to divinate the eternal message that “dresses are for women” out of thin air (or maybe directly from Allah), and that same dumb baby also has the ingenuity to cleverly repurpose their onesie into a jury-rigged “dress”. I’m not claiming that it’s impossible for young children to notice and even mirror societal expectations, including gender-related ones. Indeed, research indicates wisps of this awareness can start manifesting very early on, with children reaching “peak rigidity in their gender stereotypes at age 5 to 6” followed by a dramatic and continuing increase in flexibility. But it remains a jaw-dropping level of projection and tea leaf–reading on display here by Dr. Ehrensaft; the simple explanation that a baby might open their onesie because they’re a dumb baby is apparently not worth consideration.

Dr. Ehrensaft is illustrative of the intellectual rigor that is apparently expected from the lead mental health professional in charge of the well-being of an entire clinic’s worth of young patients. Matt Osborne wrote a devastating piece about her very long history of dangerous quackery. My mind was blown when I found out that Dr. Ehrensaft happened to be at the scene in 1992 desperately trying to whitewash the Daycare Satanic Panic and the unconscionable misery the “recovered memory” movement caused. In response to some highly suggestive interviews by therapists, preschool children alleged bizarre and horrific sexual abuse by staff involving drills, flying witches, underground tunnels, and hot-air balloons. The notorious McMartin case resulted in no convictions, with all charges finally dropped in 1990 after seven years of prosecutions. Two years later in an aftermath report of the similar Presidio case, Dr. Ehrensaft notes how the children’s abuse narratives often contained fantasy elements, such as devilish pranks and hidden skeletons. This should normally be grounds for skepticism, but Dr. Ehrensaft stridently refuses to question the veracity of the accounts, and explains away the outlandish aspects as simply the result of trauma management — the kids were using imaginative fears as a protective barrier for their (according to Dr. Ehrensaft) unquestionably real trauma. Given her general credulity, it’s no surprise why her writing on the topic of gender identity is a murky soup of pseudo-religious nonsense about “gender ghosts” and “gender angels”.

What exactly is the explanation for trans-affirming professionals like Chappell and Ehrensaft explicitly encouraging the necessity of adhering to gender scripts? Were they misled? Did they get the wrong bulletin? How? Why aren’t their professional peers correcting them on such an elementary and foundational error? So many questions.

You can’t keep drawing from the well of gender stereotypes so blatantly without anyone noticing. My general impression of the field is people realized how idiotic they sounded when their talking points were solidly anchored upon the veneration of (purportedly antiquated) gender roles and gender scripts. The response to this inescapable criticism has largely been to subtly pivot into the realm of empty rhetoric. But because of the necessity to cling onto strands of the initial assertions (for reasons I’ll explain further), the result is a strenuous ballet of either constantly leaping between the two positions, or uncomfortably trying to straddle both.

Dr. Ehrensaft gives us an example of the vacuous. Her onesie/barrette poem of an answer above is from a video uploaded in 2018, but here’s how her website explains gender nowadays, except with one particular word switched out:

This core aspect of one’s identity comes from within each of us. Flibberdibber identity is an inherent aspect of a person’s make-up. Individuals do not choose their flibberdibber, nor can they be made to change it. However, the words someone uses to communicate their flibberdibber identity may change over time; naming one’s flibberdibber can be a complex and evolving matter. Because we are provided with limited language for flibberdibber, it may take a person quite some time to discover, or create, the language that best communicates their internal experience. Likewise, as language evolves, a person’s name for their flibberdibber may also evolve. This does not mean their flibberdibber has changed, but rather that the words for it are shifting.

Can anyone reading this tell me what flibberdibber is beyond that it’s something inexplicably very important?

It’s probably too much to expect philosophy to throw us a lifeline here, but even with those low standards, the response from the trans-inclusionary philosophers has been a complete fucking mess and followed a similarly strenuous pivot. For example, in the 2018 paper Real Talk on the Metaphysics of Gender, Yale philosopher Robin Dembroff argues for a more “inclusive” understanding of gender. But in doing so, Dembroff explicitly acknowledges the glaring contradiction between decrying a category as oppressively exclusionary while simultaneously petitioning to be included within it. The apparent solution on page 44 to this conundrum is rather. . . something:

First, when people use terms like ‘man’ differently, they often engage in substantive disagreement about who ought to have the robust associations welded to that particular gender classification. Even if two people use the same word (‘man’) to pick out different gender kinds, and respectively claim that Chris is a man [trans-inclusive-kind] and is not a man [dominant-kind], their dispute is not merely verbal. They disagree about whether Chris—and people like Chris—should be conferred the social associations that come with being classified as a man in the immediate context.

Second, when someone in a dominant context eschews the operative gender kinds, and instead classifies gender according to trans-inclusive kinds, they implicitly provide an internal critique of the ideology that sustains dominant gender kinds. More specifically, they imply that dominant gender kinds—despite a pervasive myth of their universality and immutability—are contingent and malleable. They could have been or could become otherwise.

Dembroff acknowledges the [dominant-kind] meaning of ‘man’ is regressively stifling, but argues that if enough people use the [trans-inclusive-kind], then the meaning of ‘man’ can be shifted to achieve inclusion. Well, yes, and if my grandmother had wheels she would’ve been a bike. Other trans-inclusionary philosophers offer a similarly garbled effort with “ameliorative inquiry”. The goal from the outset is a revision of the definition of ‘woman’ explicitly to be more “inclusive”:

An ameliorative inquiry into the concept of woman invites feminists to consider what concept of woman would be most useful in combatting gender injustice. This opens the way for a revisionary analysis that can be tailored to avoid exclusion and marginalization.

As Tomas Bogardus pointed out, the glaring contradiction remains: You cannot anchor the definition upon biological sex because that would be trans-exclusionary, but you also cannot anchor the definition upon gender stereotypes because that would be regressive and publicly humiliating. The irreconcilability explains why so much energy within the field of philosophy is devoted toward suppressing inquiries rather than resolving them, as Alex Byrne experienced in his attempts to write on the subject.

Trans-inclusionary philosophers realize how stifling it is to be bound to specific vocabulary, but for whatever reason, instead of charting a new lexicon, they hold on to the chain. The only possible explanation for this unrelenting dedication is to maintain access to what Dembroff refers to as “the robust associations welded to that particular gender classification.” Stereotypes, in other words. It’s also the only explanation for why the circular definition “a woman is someone who identifies as a woman” garners so much intense attachment despite its emptiness. It maintains the ability to hint-hint-wink-wink toward gender stereotypes without having to say so out loud.

Throughout the course of my research on this topic I tried to limit myself to authority figures within the field of transgender health, but it hasn’t been a helpful filter. For example, the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) expressed a similar comfort with gendered expectations in their 7th edition Standards of Care published back in 2012. On page 5, WPATH offers a confused warning about how gender nonconformity should not necessarily be equated with gender dysphoria, but then goes on to say (emphasis added):

Treatment is available to assist people with such distress to explore their gender identity and find a gender role that is comfortable for them. . . . Hence, while transsexual, transgender, and gender nonconforming people may experience gender dysphoria at some point in their lives, many individuals who receive treatment will find a gender role and expression that is comfortable for them, even if these differ from those associated with their sex assigned at birth, or from prevailing gender norms and expectations.

2012’s WPATH was therefore deliberately embracing gender roles as a serviceable structure, potentially as a palliative remedy. Part of their goal then was explicitly about finding the “right” gender role for a person, whatever that means. Compare that language above with SOC 8 (2022) on page S6, where the equivalent section now omits any mention whatsoever of gender roles. The effacement, however, was not absolute, because within the same section WPATH attributes symptoms of transgender psychological distress not as inherent to being transgender, but instead entirely the fault of social stigma. This implicitly maintains the framing of gender transition as a sort of “appeasement” intended to mollify societal expectations, which makes sense only if you assume the expectations are worth acquiescing to.

Not even diagnostic manuals intended for psychiatric professionals are there to offer any clarity. Here’s part of what the DSM-5 lists as criteria for gender dysphoria (emphasis added):

A marked incongruence between one’s experienced/expressed gender and primary and/or secondary sex characteristics

A strong desire to be rid of one’s primary and/or secondary sex characteristics because of a marked incongruence with one’s experienced/expressed gender

A strong desire to be of the other gender

A strong desire to be treated as the other gender

A strong conviction that one has the typical feelings and reactions of the other gender

Except for the last point, which is explicitly anchored within stereotypes (“typical feelings and reactions”), the other entries on this list are so devoid of meaning. What does it mean to be “treated as the other gender”? What does it feel like to experience a “marked incongruence”? I definitely have an answer in mind and it rhymes with “high as a kite” but supposedly that’s wrong. Again, if it’s not that, then what??

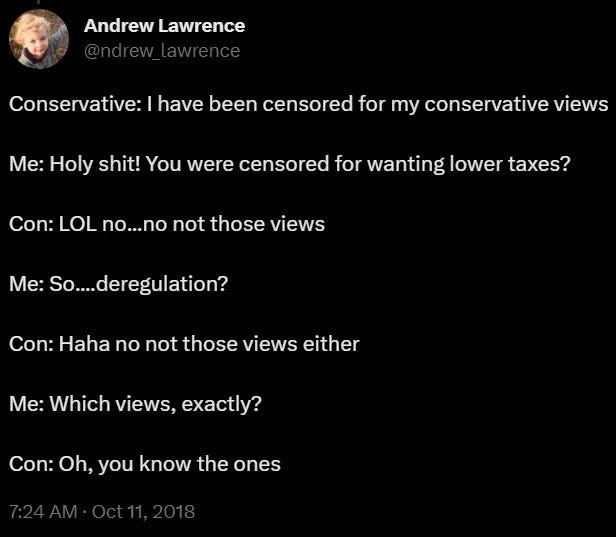

I’m reminded of a tweet:

I spent so long assuming I misunderstood something and diligently looked for any training materials intended to assist professionals confused by the vacuous vocabulary, but I came up empty. Is everyone in the field just pretending to understand?

Let’s assume, arguendo, that I’m an idiot. Let’s assume that the score of definitions above that I characterize as vacuous and devoid of meaning are actually perfectly coherent and I just lack the faculties to comprehend them. Let’s just assume that for now.

My question then is how did trans people not get the memo?

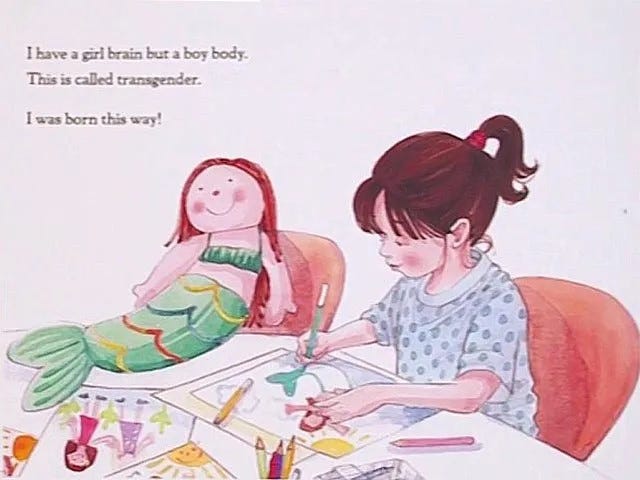

Once again I must caution that I have no idea in which way to draw the contours and avoid accusations of nutpicking. I will explain why I highlight the examples below, but take this disclaimer for what it’s worth. Similarly to how I previously limited myself to authorities within transgender healthcare, I tried to pick only public figures here. I Am Jazz is a children’s picture book by a reality TV star, so obviously I’m not expecting scholarly rigor here, but the message conveyed to kids from a prominent public trans figure is that liking mermaids, pink, and high heels might make you a girl.

Dylan Mulvaney has been talked about endlessly, but she continues to be heralded as a trans ambassador worthy of influence even while donning a surreal caricature of womanhood, encapsulating women as “emotionally fragile, frivolous spendthrifts, imprudent around clothes and financially inept.” Andrea Long Chu is not just any trans author, but a Pulitzer Prize winner, and her definition of the female experience from her titular book on the subject includes absolute literary bangers like “Getting fucked makes you female because fucked is what a female is” and “femaleness to its barest essentials—an open mouth, an expectant asshole, blank, blank eyes.”

I can’t escape the feeling that I’m engaging in deplorably unsportsmanlike behavior with the mere mention of any of the preceding examples. It feels unfair in the same way it’s unfair to always bring up that time Roger mixed up the ketchup and hot sauce bottles right before the shareholder dinner every time you run into him at the annual convention in Cincinnati. If you’ve read my post on weakmanning and wondered what inspired it, there’s your answer:

Normally someone holding a belief for the wrong reasons is not enough to negate that belief. But wherever a sanewasher faction appears to be spending considerable efforts cleaning up the mess their crazy neighbors keep leaving behind, it should instigate some suspicion about the belief, at least as a heuristic. Any honest and rational believer needs to grapple for an explanation for how the crazies managed to all be accidentally right despite outfitted — by definition — with erroneous arguments.

The muckraking gets even easier if you allow yourself to go after relative nobodies. The video What is a Woman: Wrong Answers Only is blatantly intended to be a piece of disturbing agitprop showcasing a cavalcade of (allegedly) transwomen equating the experience of womanhood with vapid airhead bimbo archetypes, and much much worse. The examples highlighted are undoubtedly cherry-picked and intended to maximize outrage, but it nevertheless remains true that a significant number of trans individuals earnestly describe their experience using vocabulary that is indistinguishable from some of the most degrading gender caricatures.

Obviously no one is obligated to “answer for” any of the above examples, but just like the questions about trans-affirming professionals earlier, what the fuck is the explanation here? Are the folx above deluded about their transness or otherwise faking it? Are they crisis actors hired by Matt Walsh? Are they actually trans but somehow received the wrong bulletin about how to talk about the trans experience? How the fuck does that happen? Someone throw me a lifeline and please explain this to me, because I’m not seeing any other answers that make sense.

I made my argument and showed you my receipts; now let’s tear it down. The glaring weakness in my position is that I have no explanation for why gender stereotypes should make a comeback, nor why it would be agitated for by society’s most progressive cohort. I’ll present some theories but they’re admittedly undercooked and insufficient.

Maybe it’s autism. A 2022 meta-analysis in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders demonstrates the incredibly high comorbidities between autism spectrum disorder and transgender identities, so to the extent the former is rising (and who knows why) it makes sense for the latter to rise as well. Someone with autism has a depreciated ability to “mentalize” others and a severe intolerance for social ambiguity, and perhaps adopting a rigid social script under these circumstances should be seen as a coping strategy. See, for example, how this transgender patient with autism reacts in this case study when reality goes off-script [page 279]:

JA’s difficulty with ambiguity is apparent in how he perceives others as well. He recognizes that it is custom to refer to transgender and gender nonconforming individuals by their desired gender, regardless of their appearance. But while at a large transgender event, being surrounded by countless nonbinary presentations of gender—people androgynous, genderqueer, or otherwise not matching heteronormative stereotypes, people who did not ‘‘pass,’’ or people whose presentations would seem to have contradicted their pronoun choices—left him overwhelmed with anxiety.

Another theory is that gender identity is indeed fake, but even if it’s fiction, maybe it’s useful fiction. I’ve made this argument for all morality already, so for me it’s not much of a leap. The best way to explain this is to examine how Islamic governments, such as my birthplace of Morocco, rely upon sex segregation to police their population. Iran’s system of segregation is notoriously strict even by Muslim theocracy standards, and it’s based entirely upon the reductive assumption that all men and women must fit neatly within their prescribed social roles. Iran’s “answer” to gender nonconformity is to pretend it doesn’t exist:

The state’s authorization of sex-reassignment surgery and intolerance of homosexuality are not unrelated. “They would rather have people go under a surgeon’s knife than accepting the non-binary nature of gender,” Arastoo says. “You must either be a man or woman in your ID papers, nothing in between is recognized.”

Just like when President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad infamously claimed in 2007 that there are no homosexuals in Iran, these are the soothing lies Iranian society relies upon to maintain its structural integrity. A demolition job (accepting nonconformity) jeopardizes far too much, so it settles for a shoddy patch-up (enforcing conformity).

Our modern cosmopolitan society is particularly prone to fictions with how we describe mental health conditions. In Trans Is Something We Made Up, 21st Century Salonnière describes how universal experiences get shoehorned into culturally specific configurations:

Take windigo [morbid state of anxiety over becoming a cannibal], for example. The modern Western take seems to be something like this: Windigo and the extreme anxiety associated with it are real. Humans are wired to experience anxiety, and human behavioral traits exist on a spectrum. Therefore, a few unfortunate outliers in every culture, in every time and place, will experience extreme anxiety. The cannibalism thing, though, is something that a particular culture layered on top. It’s very real to the sufferers, but it’s also true that a culture “made it up.” Other cultures tell the story about their anxiety in different ways. They express and experience their anxiety in other ways. The cannibalism thing represents one culture telling a story about anxiety.

Salonnière quotes the psychiatrist Ronald Simons, who said “Unlike objects, people are conscious of the way they are classified, and they alter their behavior and self-conceptions in response to their classification.”

Jessica Taylor grappled with similar concerns over the “gender identity” paradigm in her highly recommended and insightful post Am I trans? (emphasis added):

Most of what feelings like this (and others that made me think I might be trans) indicate is that I had/have a strong preference for having a female body and living as a woman; “dysphoria” may in some cases be a way of communicating this kind of preference to people and social systems that only care about sufficiently negative conditions, such as much of the medical system. Unfortunately, requiring people to provide “proof of pain” to satisfy their strong preferences may increase real or perceived pain as a kind of negotiating strategy with gatekeeping systems that are based on confused moral premises.

Scott Alexander wrote about this in his allegory about the penis-stealing witches. Right now we have drugs that some people want, but the medical establishment keeps them locked up inside a cabinet. Absolute individual autonomy around substance consumption and body modifications is apparently too radical a notion, so access to controlled substances is handled through the completely fictional framework of requiring a medical diagnosis. So if you want legal meth, for example, an ADHD diagnosis happens to be the currently approved social ritual to gain that access.

I admit a degree of hubristic naivety whenever I propose replacing a social structure with a greenfield alternative out of thin air. While I personally would love to see all drugs available through vending machines, including cross-sex hormones, I can’t just will that reality into existence. Although I’m very much in favor of encouraging gender nonconformity, I’m absolutely not a blank-slatist on the question of sex — there are clear observable differences in physiology and psychology between males and females that will not disappear any time soon.

So perhaps modern society’s continuing perseverance with gendered expectations — whether by Bay Area clinicians or by Iranian clerics — is a sign that the rigidity remains far too useful to abandon, no matter what self-serving tales we might tell otherwise. This doesn’t explain everything, but it’s the most earnest effort I can deliver on this front.

Special thanks to my amazing copy editor for pointing out Dr. Ehrensaft’s Satanic Panic history and forcing me to add even more to the already insane word count. Immense gratitude as well to Autumn for some very thoughtful and substantive feedback.

I've always bristled at the fact that opposing gender ideology is seen as a conservative issue, when it can be framed as a progressive one. The fact that gender ideologues are forced to resort to stereotypes is a very regressive choice.

https://societystandpoint.substack.com/p/i-am-a-true-progressive

Here come the new gender stereotypes, same as the old gender stereotypes:

https://thecritic.co.uk/here-come-the-new-gender-stereotypes-same-as-the-old-gender-stereotypes/